Paul 1 and Napoleon. Paul I is the pioneer of the “continental blockade. Features of cultural development in the 18th century

In the previous decade, the 1790s, European politics were fairly clear. The monarchies of Europe united to destroy the new state system - the republic. The principle proclaimed by the French “Peace to huts, war to palaces” should not have infected other countries. Each monarch saw his possible fate in the severed head of Louis XVI. But the revolution gave rise to an unprecedented impulse among the French people - it was not possible to break the republic, and the allies in the anti-French coalitions were not friendly.

After Suvorov's campaign in 1799, it became clear that Russia and France gained nothing from the conflict with each other. This war was beneficial to England, Austria and Prussia, who wanted to pull chestnuts out of the fire with Russian hands. There was no direct clash of the real interests of Russia and France either before or after 1799. Apart from the restoration of the monarchy in France, there was really nothing for Russia to fight for. In the unfolding European conflict, it was in the interests of both great powers to have an alliance or at least benevolent neutrality towards each other. Bonaparte understood this well and took up the issue of rapprochement with Russia as soon as he became first consul. Paul I came to the same thoughts in 1800: “As for rapprochement with France, I would like nothing better than to see her resorting to me, especially as a counterweight to Austria.”

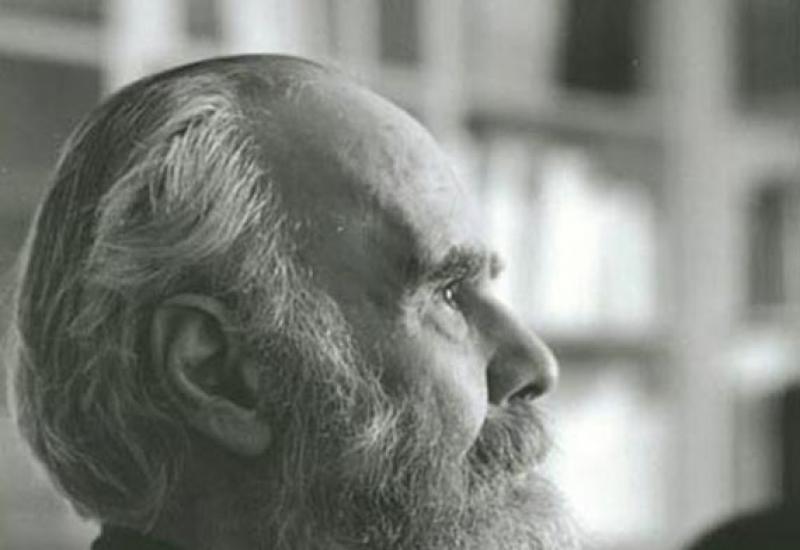

Emperor Paul I

An important factor for the Russian emperor was the enmity of France and Britain, which irritated him. The British ambassador in St. Petersburg, Whitworth, was so alarmed that he wrote: “The Emperor is, in the full sense of the word, out of his mind.” Both rulers, Paul and Napoleon, understood the commonality of their interests in European politics: France needed an ally in the fight against the great powers surrounding it, Russia needed to at least stop fighting for other people's interests.

But there were also obstacles to this successful solution. There was no doubt that England would do its best to prevent the rapprochement between France and Russia. And the conservatism of Russian public opinion, which did not want rapprochement with the Republicans, also initially inclined Pavel to postpone this. The agreement with Bonaparte meant a sharp deterioration in relations with England and France. But since their treacherous and selfish policies of the allies made a strong negative impression on Paul, in the end he, a supporter of the principle of legitimism, a representative of a large European house, nevertheless decided to draw closer to revolutionary France. A bold and risky step. But he saw in Bonaparte something that rulers of other countries often lacked - a willingness to see the interests of a partner.

Napoleon Bonaparte

The chivalric spirit brought Paul I and Napoleon closer together

In March 1800, Paul ordered the suspension of all military actions against France. Already in the summer, Bonaparte proposed to Russia that all prisoners (about 6 thousand) be returned to Russia free of charge and without conditions, in new uniforms, with new weapons, with banners and honors. This step, filled with a noble chivalric spirit, was very sympathetic to Paul I. In addition, Bonaparte promised Paul, the Grand Master of the Knightly Order of Malta, to defend Malta with all his might from the British.

Paul saw this as a sincere desire for agreement. And then he sent an ambassador, General Sprengporten, to Paris. He was received with honor, and especially friendly by Bonaparte himself. The parties now openly informed each other that they see a great many common interests and too few reasons for enmity. France and Russia “were created geographically to be closely connected,” Bonaparte said. Indeed, powers distant from each other had no reasons for conflict that would arise from their geographical location. There were simply no serious and insoluble contradictions. The expansion of both countries went in different directions.

St. Petersburg at the beginning of the 19th century

“France can only have Russia as an ally,” Bonaparte said. In fact, there was no better choice. France and England were irreconcilable. But they could not defeat their friend - the English fleet was too strong, and the French ground forces were too strong. And the scales could tip in favor of one of the parties only with an alliance with Russia. Pavel wrote to Sprengporten: “...France and the Russian Empire, being far from each other, can never be forced to harm each other,...they can, by uniting and constantly maintaining friendly relations, prevent others from being harmed by their desire for conquest and domination their interests." Changes in the internal politics of France, the appearance of the first consul and the respect he showed towards Russia also smoothed out previous disagreements caused by the different political structures of these states.

This was all especially bold for Paul, who was surrounded by many opponents of Franco-Russian friendship, who later became his murderers. Both Austria and especially England tried to keep Paul from taking this step. The British generally offered Russia the conquest of Corsica, hoping to quarrel with France and the Corsican Napoleon forever. But the Emperor of Russia ignored all attempts by the Allies to spoil the emerging agreements. In December 1800, he personally wrote to Bonaparte: “... I do not speak and do not want to argue either about human rights or about the principles of various governments established in each country. We will try to return to the world the peace and quiet that it so needs.” This meant that from now on Russia did not want to interfere in the internal affairs of the republic.

Paris at the beginning of the 19th century

Russian soldiers could wash their boots in the Indian Ocean in 1801.

In St. Petersburg, plans were already being made to benefit from such a grandiose undertaking as an alliance with Napoleon: for example, the division of decrepit Turkey between Russia, France, Austria and Prussia. In turn, inspired by his unexpected and fairly rapid diplomatic success, Bonaparte at the beginning of 1801 fantasized about expeditions against Ireland, to Brazil, India and other English colonies.

Sustainable cooperation with Russia also opened the way for Bonaparte to conclude a fragile, but still peace with Austria and England. Peace provided an opportunity to prepare for the resumption of the struggle and enter into it with new strength.

The strengthening of England and its capture of Malta caused Paul great irritation. On January 15, 1801, he already wrote to Napoleon: “... I cannot help but suggest to you: is it possible to do something on the shores of England.” This was already a decision on an alliance. On January 12, Pavel ordered the Donskoy army to raise regiments and move them to Orenburg, in order to then defeat India (more than 20 thousand). France was also preparing to send 35 thousand people on this campaign. Napoleon's dreams were close to coming true - England would not have withstood such a blow, its prestige would have collapsed and the flow of money from the richest colony would have stopped.

Alexander the First

Mikhailovsky Castle, place of death of Paul I

England killed the Russian emperor for an alliance with Napoleon

But when the Cossack regiments were already marching in the direction of the “pearl of the British crown,” India, and Napoleon was anticipating the successes of the Franco-Russian alliance and making new plans, Europe was struck by unexpected news - Paul I was dead. No one believed the official version of the apoplexy that allegedly took Paul’s life on the night of March 12. Rumors spread about a conspiracy against the emperor, which happened with the support of Tsarevich Alexander and the English ambassador. Bonaparte perceived this murder as a blow dealt to him by the British. Not long before this, they had tried to kill him himself, and he had no doubt that England was behind it. Alexander I understood that his environment expected him to adopt a policy radically different from his father’s. This implied both a break with France and a return to a pro-English political course. Almost immediately, the troops moving towards India were stopped. And yet, for a long time Napoleon would strive for an alliance with Russia, without which the fate of Europe could not be decided.

Paul I, who regarded the behavior of the English and Austrian allies as a representation, recalled the Russian army to Russia. Soon (after Napoleon Bonaparte, who returned from the Egyptian campaign, carried out a coup d'etat and proclaimed himself first consul), Paul broke the alliance with England and Austria and entered into an alliance with France. The first consul captivated the Russian emperor with the prospect of a joint campaign in India. However, the alliance with France was extremely unpopular in Russia, since the nobility saw Napoleon as the heir to the revolution and the usurper of the Bourbon throne. A sharp turn in foreign policy was one of the reasons for the overthrow and murder of Paul I as a result of a palace coup on March 11-12, 1801. The new Tsar Alexander I broke the alliance with France.

What to pay attention to when answering:

In the course of the answer, the close connection between the southern and western directions of Russian foreign policy should be demonstrated.

Speaking about the victories of Russian weapons and their significance for the development of Novorossiya and Russia’s access to sea routes, one should still not forget about the aggressive, imperial nature of Catherine II’s foreign policy.

The answer requires constant careful work with the map, which should show all the named territories and battle sites.

1 The literal translation is free prohibition.

2 On the southern borders, Russia did not yet have a fleet: it was impossible to create it in the shallow Azov Sea, and the shores of the Black Sea belonged to Turkey.

3 The purpose of this union was to implement the so-called “Greek project” - the dismemberment of Turkey and the creation of a “Greek Empire” led by a representative of the Romanov dynasty on its territories with an Orthodox population.

4 During the partitions of Poland, Russia annexed territories with predominantly Ukrainian and Belarusian populations, most of them Orthodox. However, this cannot justify the division of a sovereign state in which Ukrainians and Belarusians have lived for centuries. In addition, the Russian Empire also included lands inhabited by Catholics: Poles and Lithuanians, and Lutherans - Latvians. Subsequently, after the defeat of Napoleon, Russia achieved the transfer to it of a significant part of the Polish lands that had previously gone to Prussia. In exchange for this, Russia supported Prussia, which sought to annex as many territories of other German states as possible.

5 Northern Italy was conquered by General Bonaparte (future First Consul and Emperor Napoleon I) in 1797 during the so-called “First Italian Campaign”.

Topic 42.

CULTURE OF RUSSIA IN THE MIDDLE AND II HALF OF THE 18TH CENTURY

1. Features of the development of culture in the 18th century

The reforms of Peter I created an unusual cultural situation in Russia. Europeanization, which affected only the upper strata of society, led to the emergence of a deep cultural gap between the nobility and the bulk of the country's population. In Russia, two cultures emerged: the dominant one, closely aligned with the European one, and the folk one, which remained predominantly traditional.

2. Life

In the 18th century Most of the peasants still lived in huts, heated in black. True, the design of the hut has changed: a wooden floor and ceiling appeared. In the winter, young livestock were kept in the hut along with people. Overcrowding and lack of hygiene led to high mortality, especially among children.

The vast majority of serfs were illiterate. In the state-owned villages, the proportion of literate people was slightly higher, reaching 20-25%.

Leisure, which usually appeared only in winter, after agricultural work was completed, was filled with traditional entertainment: songs, round dances, get-togethers, and ice slides. Family relationships also remained traditional. As before, contrary to the decree of Peter I, the decision to marry was made not so much by young as by older family members, and sometimes by the master.

The life of a rich landowner had nothing in common with the village. The costume, interior of the home, and the landowner's daily table differed from the peasants' not only in wealth, as in the 16th-17th centuries, but in the type itself. The landowner wore a uniform, a camisole, and later a tailcoat, and kept a cook who prepared delicious dishes (rich nobles hired cooks from abroad). Rich estates had numerous servants, including not only footmen and coachmen, but their own shoemakers, tailors and even musicians. However, this applies to the rich and noble elite of the nobility. Small landed nobles had much more modest opportunities and demands.

Even at the end of the 18th century. only a few nobles were well educated. And yet, it was the estate life, freedom from material need and official duties (after the Manifesto “On the Freedom of the Nobility”) that ensured the flourishing of culture in the second half of the 18th and 19th centuries.

“Hindustan is ours!” and “a Russian soldier washing his boots in the Indian Ocean” - this could have become a reality back in 1801, when Paul I, together with Napoleon, attempted to conquer India.

Impenetrable Asia

As successful as Russia's exploration of the east was, it was just as unsuccessful in the south. In this direction, our state was constantly haunted by some kind of fate. The harsh steppes and ridges of the Pamirs always turned out to be an insurmountable obstacle for him. But it was probably not a matter of geographical obstacles, but a lack of clear goals.

By the end of the 18th century, Russia was firmly entrenched in the southern borders of the Ural range, but raids by nomads and intractable khanates hindered the empire’s advance to the south. Nevertheless, Russia looked not only at the still unconquered Emirate of Bukhara and the Khanate of Khiva, but also further - towards the unknown and mysterious India.

At the same time, Britain, whose American colony had fallen away like ripe fruit, concentrated its efforts on India, which occupied the most important strategic position in the Asian region. While Russia was stalling on its approach to Central Asia, England, moving further north, was seriously considering plans to conquer and populate the mountainous regions of India, favorable for farming. The interests of the two powers were about to collide.

"Napoleonic plans"

France also had its own plans for India. However, it was not so much interested in the territories as in the hated British, who were strengthening their rule there. The time was right to knock them out of India. Britain, torn by wars with the principalities of Hindustan, noticeably weakened its army in this region. Napoleon Bonaparte had only to find a suitable ally.

The First Consul turned his attention to Russia. “With your master, we will change the face of the world!” Napoleon flattered the Russian envoy. And he was right. Paul I, known for his grandiose plans to annex Malta to Russia or send a military expedition to Brazil, willingly agreed to a rapprochement with Bonaparte. The Russian Tsar was no less interested in French support. They had a common goal - to weaken England.

However, it was Paul I who first proposed the idea of a joint campaign against India, and Napoleon only supported this initiative. Paul, according to historian A. Katsura, was well aware “that the keys to mastery of the world are hidden somewhere in the center of the Eurasian space.” The eastern dreams of the rulers of two strong powers had every chance of coming true.

Indian blitzkrieg

Preparations for the campaign were carried out in secret, all information was mostly transmitted orally through couriers. The joint push to India was allotted a record time of 50 days. The Allies relied on the support of the Maharaja of Punjab, Tipu Said, to speed up the expedition's progress. From the French side, a 35,000-strong corps was to march, led by the famous General Andre Massena, and from the Russian side, the same number of Cossacks led by the ataman of the Don Army, Vasily Orlov. In support of the already middle-aged ataman, Pavel ordered the appointment of officer Matvey Platov, the future ataman of the Don Army and a hero of the War of 1812. In a short time, 41 cavalry regiments and two companies of horse artillery were prepared for the campaign, which amounted to 27,500 people and 55,000 horses.

There were no signs of trouble, but the grandiose undertaking was still in jeopardy. The fault lies with the British officer John Malcolm, who, in the midst of preparations for the Russian-French campaign, first entered into an alliance with the Afghans, and then with the Persian Shah, who had recently sworn allegiance to France. Napoleon was clearly not happy with this turn of events and he temporarily “froze” the project.

But the ambitious Pavel was accustomed to completing his undertakings and on February 28, 1801, he sent the Don Army to conquer India. He outlined his grandiose and bold plan to Orlov in a parting letter, noting that where you are assigned, the British have “their own trading establishments, acquired either with money or with weapons. You need to ruin all this, liberate the oppressed owners and bring the land into Russia into the same dependence as the British have it.”

Back home

It was clear from the outset that the expedition to India had not been properly planned. Orlov failed to collect the necessary information about the route through Central Asia; he had to lead the army using the maps of the traveler F. Efremov, compiled in the 1770s - 1780s. The ataman failed to gather an army of 35 thousand - at most 22 thousand people set out on the campaign.

Winter travel on horseback across the Kalmyk steppes was a severe test even for seasoned Cossacks. Their movement was hampered by burkas wet from melted snow, rivers that had just begun to become free of ice, and sandstorms. There was a shortage of bread and fodder. But the troops were ready to go further.

Everything changed with the assassination of Paul I on the night of March 11-12, 1801. “Where are the Cossacks?” was one of the first questions of the newly-crowned Emperor Alexander I to Count Lieven, who participated in the development of the route. The sent courier with the order personally written by Alexander to stop the campaign overtook Orlov’s expedition only on March 23 in the village of Machetny, Saratov province. The Cossacks were ordered to return to their homes.

It is curious that the story of five years ago repeated itself, when after the death of Catherine II the Dagestan expedition of Zubov-Tsitsianov, sent to the Caspian lands, was returned.

English trace

Back on October 24, 1800, an unsuccessful attempt was made on Napoleon's life, in which the British were involved. Most likely, this is how English officials reacted to Bonaparte’s plans, afraid of losing their millions that the East India Company brought them. But with the refusal to participate in Napoleon’s campaign, the activities of English agents were redirected to the Russian emperor. Many researchers, in particular the historian Kirill Serebrenitsky, see precisely English reasons in the death of Paul.

This is indirectly confirmed by facts. For example, one of the developers of the Indian campaign and the main conspirator, Count Palen, was noticed in connections with the British. In addition, the British Isles generously supplied money to the St. Petersburg mistress of the English ambassador Charles Whitward so that, according to researchers, she would prepare the ground for a conspiracy against Paul I. It is also interesting that Paul’s correspondence with Napoleon in 1800-1801 was bought in 1816 by a private individual from Great Britain and was subsequently burned.

New perspectives

After the death of Paul, Alexander I, to the surprise of many, continued to improve relations with Napoleon, but tried to build them from positions more advantageous for Russia. The young king was disgusted by the arrogance and gluttony of the French ruler.

In 1807, during a meeting in Tilsit, Napoleon tried to persuade Alexander to sign an agreement on the division of the Ottoman Empire and a new campaign against India. Later, on February 2, 1808, in a letter to him, Bonaparte outlined his plans as follows: “If an army of 50 thousand Russians, French, and perhaps even a few Austrians headed through Constantinople to Asia and appeared on the Euphrates, it would make England and would have brought the continent to its feet.”

It is not known for certain how the Russian emperor reacted to this idea, but he preferred that any initiative come not from France, but from Russia. In subsequent years, already without France, Russia begins to actively explore Central Asia and establish trade relations with India, eliminating any adventures in this matter.

One must fear enemies when they are far away,

so as not to be afraid of them when they are close.

J. Bossuet.

The relationship between Russia and Napoleonic France began under Emperor Paul I.

Paul's policy, external and internal, was determined by an old-fashioned sense of knightly honor. He wanted to be a monarch whose actions were determined not by “interests”, not by “benefit”, especially not by the “will of the people”, but exclusively by the highest concepts of honor and justice.

Pavel in the costume of the Grand Master of the Order of Malta

It was these considerations that prompted him to join the second anti-French coalition (1799-1802, consisting of England, Turkey, Austria, the Kingdom of Naples) * , and also become a grand master of the Order of St. John of Jerusalem, or the so-called Order of Malta. At that time, the Order was going through hard times. His commanderies in various European countries were closed or confiscated, and Malta itself was under threat of capture by France or England. By the will of Paul, everything changed: not only the foreign commanderies of the order were restored, but also new ones appeared - in Russia itself.

* The first coalition of European states against France (England, Prussia, Naples, Tuscany, Austria, Spain, Holland) was formed back in 1792 . and existed until 1797.

However, patronage of the Order of Malta soon led to a break with the main coalition ally - England, which in 1800, contrary to the promises made, captured Malta and thus inflicted a personal insult on Paul.

At the same time, Paul also quarreled with Austria, which, having regained Italy with the help of Russian troops, was not at all eager to restore the French throne, and yet it was for this purpose that Suvorov was sent to help the Austrians.

The consequence of this unchivalrous behavior of the allies was a drastic change in the entire foreign policy of Russia. True, Paul himself did not think so. In a conversation with the Danish ambassador, he said that “his policy has remained unchanged for three years now and is connected with justice where His Majesty believes to find it; for a long time he was of the opinion that justice was on the side of the opponents of France, whose government threatened all powers; now a king will soon be established in this country, if not in name, then at least in essence, which will change the state of affairs...”

We must pay tribute to Paul's insight: the true essence of the coup d'etat of the 18th Brumaire of 1799 in France did not escape him * . He was one of the first in Europe to understand the difference between Jacobin France and the Consulate. The Tsar looked with sympathy at the young First Consul, whose ambitious intentions still remained a secret to many Frenchmen.

Napoleon - First Consul

And in Russian society, initially the name of Napoleon, “who killed the monster of revolution,” was pronounced, rather, with sympathy, as a person who “deserved the eternal gratitude of France and even Europe” (N.M. Karamzin, “A Look at the Past Year”). Young people looked at him as their idol. A graduate of the Land Cadet Corps, S.N. Glinka, recalled the years of his youth: “With Napoleon sailing to the shores of Egypt, we followed the exploits of the new Caesar; we thought of his glory; through his glory a new life blossomed for us. The height of our desires then was to be among the ordinary rank and file under his banners. But we were not the only ones who thought so and we were not the only ones who strived for this. Whoever from his youth became acquainted with the heroes of Greece and Rome was then a Bonapartist.”

* 18 Brumaire (November 9), 1799 Napoleon dispersed the deputies of the Legislative Corps and announced the abolition of the Directory regime. Power passed to the Executive Consular Commission, consisting of three consuls. Napoleon assumed the official title of First Consul.

The Russian emperor did not limit himself to leaving the coalition. Together with Prussia, Sweden and Denmark, he formed a league of neutral states in order to jointly oppose England in the Baltic. England's retaliation for Malta was the embargo imposed by Paul on English ships and goods in all Russian ports. At the same time, the Tsar ordered Count F.V. Rostopchin, who actually headed the Collegium of Foreign Affairs, to express his thoughts on the political state of Europe.

Fyodor Vastlyevich Rostopchin

Rostopchin presented a memorandum to the Tsar, not suspecting that this document would not only make important changes in politics, but also serve as the basis of a new political system. Pavel kept this document for two days and returned it to the author with the resolution: “I’m trying it out.” * your plan in everything, I wish you to begin to fulfill it: God grant that it will be according to this!”

*I approve, I approve (fromlat.approbare — officially approve, confirm, publish).

The main idea of Rostopchin's note was a close alliance with France (that is, with Napoleon) for the division of Turkey, which was supposed to destroy England's influence in the Mediterranean and the Middle East. It was supposed to attract Austria and Prussia to the division, tempting the first with Bosnia, Serbia and Wallachia, and the second with some North German lands. Russia, Rostopchin wrote, can count on Romania, Bulgaria and Moldova, “and in time the Greeks themselves will come under the Russian scepter.” Pavel liked this idea, and he wrote in the margin: “Or you can fail.”

Rostopchin spoke extremely disapprovingly of England, saying that “with its envy, cunning and wealth, it was, is and will remain not a rival, but a villain of France.” In this place, the Tsar added approvingly: “Masterfully written!”, and where the author of the note was spreading the fact that England had armed “all powers” against France, he sadly wrote: “And us sinners.”

Napoleon, who himself was looking for an ally in the fight against England, in turn, shrewdly guessed how he could arouse Paul’s sympathy. Demonstrating his good relations with Russia, he ordered the unconditional release of six thousand Russian prisoners captured by French troops in the Italian-Swiss campaign of 1799-1800. The soldiers returned home, dressed at the expense of the French treasury in new uniforms, with weapons and banners. In a conversation with the Russian ambassador Count E.M. Sprengtporten, the first consul promised to recognize the rights of the Russian emperor to Malta and especially emphasized that the geographical position of Russia and France obliges both countries to live in close friendship. In addition, Napoleon sent Paul a handwritten letter, in which he assured the Tsar that if he sent him his confidant with the necessary powers, then in twenty-four hours peace would reign on the continent and on the seas.

Napoleon's chivalrous act towards the Russian prisoners charmed Paul. He ordered portraits of the first consul to be hung in his palace and publicly drank to his health. In a response letter to Napoleon, sent together with Ambassador Plenipotentiary S.A. Kolychev, the Tsar showed the height of generosity and condescension. “I do not speak and do not want to speak either about human rights or about the fundamental principles established in each country,” he wrote. “We will try to return to the world the peace and quiet that it so needs.” In words, Kolychev, on behalf of Paul, suggested that Bonaparte accept the title of king with the right of hereditary crown, “in order to eradicate the revolutionary principles that have armed all of Europe against France.”

An alliance with Napoleon was concluded. The goals he pursued were much more consistent with the interests of France than of Russia, which would have been much more profitable to stand on the sidelines, taking advantage of the contradictions between the warring European powers. Of course, Pavel wanted to play first violin in this duet. It was not for nothing that one day, having laid out a map of Europe on his table, he folded it in two with the words: “This is the only way we can be friends.” Nevertheless, having praised Paul's insight regarding Napoleon's monarchical intentions, we have to admit that rapprochement with the first consul was a major foreign policy mistake. Acting in concert with him against England, Paul indirectly contributed to the strengthening of Napoleon's power and the growth of French influence in Europe. But, of course, in 1799, no one in Russia could have dreamed in their wildest dreams that the French army would ever stand at the Russian borders.

After Suvorov’s return from foreign campaigns in 1799, Paul 1, Emperor of Russia, broke off all diplomatic relations with England and Austria, left the alliance with them and no longer took part in the war with France. The war itself was soon stopped, since neither the British nor the Austrians, after leaving Russia, could do anything to oppose the brilliant commander, Napoleon.

Napoleon understood that the determining fact in the further development of the situation would be Russia's participation or non-participation in the war. The Emperor of France openly wrote that in the whole world there is only one ally for France - this is Russia. Napoleon openly sought an alliance with the Russians. On July 18, 1880, the French government announced that it was ready to return all prisoners of war, totaling 6 thousand people, to Russia. Moreover, the prisoners had to return in full uniform, with weapons and banners. Paul 1, Emperor of Russia, correctly appreciated this friendly gesture of France and moved towards rapprochement with Napoleon.

Paul 1, Emperor of Russia, first of all demanded that the court of Louis 18 and the exiled French king himself leave the territory of Russia. After this, a Russian delegation was sent to France, headed by General Sperngporten. This man became the head of the delegation not by chance; he always adhered to the pro-French position. As a result, the contours of a possible alliance between Russia and France began to be clearly visible for the first time.

At this time, the British began to actively act in order to keep Paul 1 from an alliance with Napoleon. They suggested that the Russians once again form an alliance against France. Moreover, the conditions of the alliance were so humiliating that Paul 1, Emperor of Russia, leaned even more towards the idea of friendship with France. The British proposed a policy of non-intervention to Russia and demanded that Russian troops capture Corsica, Napoleon’s homeland.

The steps of the British only strengthened the alliance between Russia and France. Paul 1, who until that time still had doubts, finally agreed with Napoleon’s plan, who proposed to join forces and together capture India, a colony of England. It was assumed that both powers would send 35 thousand people for this campaign. On January 12, 1801, Paul 1, Emperor of Russia, gave the order to advance 41 regiments of Don Cossacks, led by Orlov, towards India.

It was a decisive time for the British government. Their world hegemony could be ended. The importance of India for England lay in the fact that India was a kind of money bag for the British. Because at that time India was the only country in the world that mined diamonds. The loss of India meant the loss of a huge amount of money for England, which in turn led to an economic crisis in Albion. And this meant the end of the British domination in the world. What happened next? On the night of March 11, 1801, he was killed in his chambers by conspirators who demanded that the emperor abdicate power. Subsequently, Alexander 1 admitted that he knew about the impending conspiracy and the involvement of the English ambassador in it. A few days before the assassination of Paul 1 in France, an unknown person tried to blow up Napoleon's carriage. Napoleon survived, but later he wrote that the conspirators missed him in Paris, but hit him in Petrograd.

Paul 1, Emperor of Russia, was killed, his successor Alexander 1 began his reign by destroying everything that his father had done. Alexander broke the alliance with France and actively began to seek the sympathy of England. A fact that suggests that Alexander 1 himself owes his throne to foreign conspirators is that the first order of Alexander 1 was to stop the Russian army, which was moving towards India. Moreover, the army was already marching and preparing to attack India.