After Charles de Gaulle. Charles de Gaulle - biography, information, personal life. List of sources and literature used

The twentieth century brought to humanity many personalities who had a tangible influence on the course of world history. One of these personalities is Charles de Gaulle.

The first president and founder of the Fifth French Republic, creator (in 1940) of the patriotic movement of the French people “Free France”, since 1941 chairman of the “French National Committee”, 1944-1946. - Chairman of the French Provisional Government.

On his initiative, a new Constitution of France was prepared and adopted by parliament in 1958. It significantly expanded the rights of the president and recognized the independence of Algeria.

This outstanding historical event began on November 22, 1890, when baby Charles was born into a family of French aristocrats in the city of Lille. The family of the future general and president was Catholic and adhered to patriotic views, which also affected the formation of the future views of Charles de Gaulle.

In 1912, after successfully graduating from the Saint-Cyr military school, he became a professional military man. In one of the battles of the First World War he was captured. In 1918 he returned to his homeland. After returning, Charles de Gaulle makes a successful military career. During this period, de Gaulle wrote several books on military and political topics.

But Charles de Gaulle truly revealed his abilities as a statesman and politician with the beginning, which he met already in the rank of general. After Marshal Henri Pétain concluded a peace truce with Germany, General de Gaulle left his homeland and on June 18, 1940, by radio from London, appealed to the French not to lay down their arms and to join the Free France movement he created.

At the beginning of the war, the main goal of the Free French was control over the territory of the French colonies. General de Gaulle coped with this task perfectly. Cameroon, Congo, Chad, Gabon, Oubangui-Shari joined the Free France. And later other colonies followed their example. At the same time, Free French fighters actively participated in Allied military operations.

In 1943, General de Gaulle became co-chairman and then chairman of the “French Committee of National Liberation” created in 1943, and remained in this post until 1946. In 1947, Charles de Gaulle founded the RPF ("Union of the French People") and joined the political struggle. But, despite more than 1 million members, the RPF did not achieve success and was dissolved in 1953.

Charles de Gaulle's finest hour came in 1958 during the Algerian crisis. The crisis paved the way for him to power. Under his leadership, the French Constitution of 1958 was developed and then adopted, which became the beginning of the Fifth French Republic, which still exists today.

Since then, France has changed from a parliamentary-presidential republic to a presidential-parliamentary republic with the president elected by popular vote. Despite strong resistance from ultra-colonialists and mutinies in the army, and a number of assassination attempts on de Gaulle, Algeria gained independence in 1962. Despite the fact that de Gaulle was a French nationalist, he fiercely defended the right of all nations and peoples to self-determination. He also came up with the idea of a united Europe.

In 1965, Charles de Gaulle was re-elected as President of France for another seven-year term. However, his new ideas did not receive support and in 1969 he resigned, completely abandoning all political activities.

Charles de Gaulle died in Colombe-les-deux-Églises, Champagne, on November 9, 1970. His grave is located in a modest local cemetery. This is the biography of one of the most famous French rulers, Charles de Gaulle.

(November 22, 1890, Lille - November 9, 1970, Colombey-les-Deux-Eglises, Haute-Marne department)

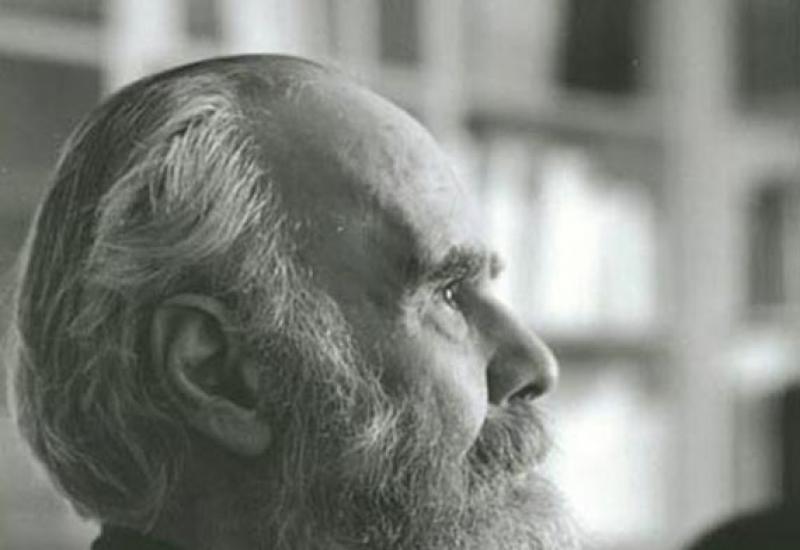

Charles de Gaulle in the BBC radio studio

Biography

In 1912 he graduated from the Saint-Cyr Military Academy. During the First World War, he was wounded three times and captured near Verdun in 1916. In 1920–1921, with the rank of major, he served in Poland at the headquarters of General Weygand's military mission. In the period between the two world wars, de Gaulle taught military history at the Saint-Cyr School, served as an assistant to Marshal Pétain, and wrote several books on military strategy and tactics. In one of them, called “For a Professional Army” (1934), he insisted on the mechanization of ground forces and the use of tanks in cooperation with aviation and infantry.

In April 1940, de Gaulle received the rank of brigadier general. On June 6 he was appointed Deputy Minister of National Defense. On June 16, 1940, when Marshal Pétain was negotiating surrender, de Gaulle flew to London, from where on June 18 he made a radio call to his compatriots to continue the fight against the invaders. Founded the Free France movement in London. After the landing of Anglo-American troops in North Africa in June 1943, the French Committee for National Liberation (FCNL) was created in Algeria. De Gaulle was first appointed its co-chairman and then its sole chairman. In June 1944, the FKNO was renamed the Provisional Government of the French Republic. After the liberation of France in August 1944, de Gaulle returned to Paris in triumph as head of the provisional government. However, the Gaullist principle of a strong executive was rejected at the end of 1945 by voters, who preferred a constitution in many ways similar to that of the Third Republic. In January 1946, de Gaulle resigned.

In 1947, de Gaulle founded a new party, the Rally of the French People (RPF), whose main goal was to fight for the abolition of the 1946 Constitution, which proclaimed the Fourth Republic. However, the RPF failed to achieve the desired result, and in 1955 the party was dissolved. In order to preserve the prestige of France and strengthen its national security, de Gaulle supported the European Reconstruction Program and the North Atlantic Treaty Organization. In the course of coordinating the armed forces of Western Europe at the end of 1948, thanks to the influence of de Gaulle, the French were given command of the ground forces and navy. In 1953, de Gaulle retired from political activity, settled in his house in Colombey-les-deux-Eglises and began writing his “War Memoirs”.

On May 13, 1958, ultra-colonialists and representatives of the French army rebelled in the Algerian capital. They were soon joined by supporters of General de Gaulle. All of them advocated keeping Algeria within France. The general himself, with the support of his supporters, skillfully took advantage of this and achieved the consent of the National Assembly to create his own government on the terms dictated by him. The first years after returning to power, de Gaulle was engaged in strengthening the Fifth Republic, financial reform, and searching for a solution to the Algerian issue. On September 28, 1958, a new constitution was adopted in a referendum. On December 21, 1958, de Gaulle was elected president. Under his leadership, France's influence in the international arena increased. Having begun to resolve the Algerian problem, de Gaulle firmly pursued a course towards Algerian self-determination. In response to this, there were mutinies of the French army and ultra-colonialists in 1960 and 1961, the terrorist activities of the Armed Secret Organization (OAS), and the assassination attempt on de Gaulle. However, after the signing of the Evian Accords, Algeria gained independence.

In September 1962, de Gaulle proposed an amendment to the constitution, according to which the election of the president of the republic should be held by universal suffrage. At a referendum held in October, the amendment was approved by a majority of votes. The November elections brought victory to the Gaullist party. In 1963, de Gaulle vetoed Britain's entry into the Common Market, blocked the US attempt to supply nuclear missiles to NATO, and refused to sign an agreement on a partial ban on nuclear weapons testing. His foreign policy led to a new alliance between France and West Germany. In 1963, de Gaulle visited the Middle East and the Balkans, and in 1964 – Latin America.

On December 21, 1965, de Gaulle was re-elected as president for another 7-year term. The long standoff between NATO reached its climax in early 1966, when the French president withdrew his country from the bloc's military organization. Elections to the National Assembly in March 1967 brought the Gaullist party and its allies a slight majority, and in May 1968 student unrest and a nationwide strike began. The President again dissolved the National Assembly and called new elections, which were won by the Gaullists. On April 28, 1969, after defeat in the April 27 referendum on the reorganization of the Senate, de Gaulle resigned.

Titles, awards and bonuses

* Grand Master of the Order of Liberation

* Order of the Elephant (Denmark)

* Order of the Seraphim (Sweden)

* Order of the Royal House of Chakri (Thailand)

Interesting Facts

General de Gaulle's address to the French 06/18/1940:

“The military leaders who led the French army for many years formed a government.

Citing the defeat of our armies, this government entered into negotiations with the enemy to end the fight.

Of course, we were suppressed and continue to be suppressed by the enemy’s mechanized ground and air forces.

What forces us to retreat is not so much the numerical superiority of the Germans, but rather their tanks, planes, and their tactics. It was the tanks, planes, and tactics of the Germans that took our leaders by surprise to such an extent that they plunged them into the position in which they now find themselves.

But has the last word been said? Is there no more hope? Has the final defeat been dealt? No!

Believe me, for I know what I say: nothing is lost for France. We will be able to achieve victory in the future by the same means that defeated us.

Because France is not alone! She's not alone! She's not alone! Behind it stands a vast empire. She can unite with the British Empire, which dominates the seas and continues to fight. She, like England, can make unlimited use of the powerful industry of the United States...

I, General de Gaulle, now in London, address the French officers and soldiers who are on British territory or who may be there in the future, armed or unarmed; to engineers and workers, specialists in the production of weapons, who are on British territory or who may find themselves there, with an appeal to establish contact with me.

Whatever happens, the flame of French resistance must not and will not go out..."

Documentation

* Acts of Free France

* De Gaulle's orders for the Normandie-Niemen squadron

Proceedings

* Professional army (in Russian, according to the 1935 edition)

* War memoirs: Conscription 1940-1942

* War memoirs: Unity 1942–1944

* War memoirs: Rescue 1944–1946

Literature

* V. N. Pchelintsev. Special mission. Chapter "General de Gaulle"

* W. Churchill. The Second World War. Chapter "Tense relations with General de Gaulle" (relationships between the Free French and the British government)

* W. Churchill. The Second World War. Chapter "Paris" (creation of the French Provisional Government during the liberation of Paris in 1944)

* V. I. Erofeev. On the history of the 1944 treaty on alliance and mutual assistance between the USSR and France

* D. F. Kraminov. In the orbit of war. Chapter 11 (creation of the French Provisional Government during the liberation of Paris in 1944; assessment of de Gaulle’s personality)

* E. Roosevelt. Through his eyes. Chapter 4. Conference in Casablanca (participation of F. D. Roosevelt in the creation of the Provisional Government led by de Gaulle)

* E d "Astier. Gods and men. 1943-1944 (Notes of the Commissioner of Internal Affairs in the government of "Fighting France")

* N. M. Kharlamov. Difficult mission (notes of a Soviet diplomat who worked with de Gaulle in London during the war)

* Romain Gary. Promise at Dawn (among other things - about the relationship between the writer and pilot Romain Gary and General de Gaulle)

Biography

He studied at the college where his father taught, and then entered the military school in Saint-Cyr.

During the First World War, Charles de Gaulle took part in hostilities, was wounded three times, and was captured near Verdun.

After the end of the war, he returned to France, graduated from the Higher Military School in Paris, and conducted military pedagogical work.

In 1940, Charles de Gaulle received the rank of brigadier general.

During the Second World War, when Germany occupied France, Charles de Gaulle crossed over to England and there took command of all French troops outside France. He founded the Free France movement, which in 1942 was renamed Fighting France.

In 1941, Charles de Gaulle headed the French National Committee, and in 1943 he became the head of the French National Liberation Committee and formed the provisional government of France.

From 1944 to 1948, Charles de Gaulle was the country's prime minister, and in 1949 he was elected president, but resigned two and a half months later.

In 1959, Charles de Gaulle again became president of France, and in the next elections, in 1964, he again won.

The activities of Charles de Gaulle were aimed at achieving the independence and independence of France in foreign policy; during his presidency, the war in Algeria, a former colony of France, was stopped; in 1966, France withdrew from NATO.

In 1969, Charles de Gaulle resigned from his post, and on November 9, 1970, he died in Colombo-les-Deux-Eglises.

Biography (L. Leonidov.)

Gaulle Charles de Gaulle Charles de (November 22, 1890, Lille, - November 9, 1970, Colombe-les-Deux-Eglises), French statesman, military and political figure. Genus. in the family of a teacher, he studied at the Saint-Cyr military school and later at the Higher Military School in Paris. Participant of the 1st World War 1914-18. Until 1937, he was mainly engaged in military pedagogical and staff activities. In the years preceding World War II (1939-45), G. made a number of theoretical works on issues of military strategy and tactics, in which he spoke out for the creation of a professional mechanized army and for the massive use of tanks in cooperation with aviation and infantry in modern warfare. From the first days of the war, de Gaulle, with the rank of colonel, commanded the tank units of the 5th French Army, and in May 1940, during the battles on the river. Somme, led the 4th Armored Division. Showed great personal courage. He was promoted to brigadier general. On June 5, a critical day for France, when a significant part of the French army had already been defeated by Nazi Germany, G. became Deputy Minister of National Defense. After the entry of German troops into Paris (June 14) and the capitulatory government of Pétain coming to power (June 16), G. went to Great Britain, from where on June 18, 1940 he addressed on the radio an appeal to all French to continue the fight against Nazi Germany. G. founded the Free France movement in London, which joined the anti-Hitler coalition, and on September 24, 1941 - the French National Committee. On September 26, 1941, the Soviet government recognized G. “as the leader of all free Frenchmen, wherever they are.” In June 1943, G. became one of two chairmen (since November 1943 - the only chairman) of the French Committee of National Liberation (FCNL), created in Algeria and reorganized in June 1944 into the Provisional Government of the French Republic (in August 1944, the government of G. moved to liberated Paris). On December 10, 1944, G. signed the Treaty of Alliance and Mutual Assistance between the USSR and France in Moscow. G.'s name is closely associated with the victory over the fascist aggressors in World War II.

Immediately after the end of the war, G. took a number of measures aimed at establishing a presidential-type regime in France. Faced with difficulties in implementing his plans, he resigned as head of government in January 1946. Since 1947, G. led the activities of the party he created, the Rally of the French People (RPF). Having announced the dissolution of the RPF in May 1953, he temporarily withdrew from active political activity. In May 1958, during a period of acute political crisis caused by the military coup in Algeria on May 13, the bourgeois majority of parliament advocated the return of Germany to power. On June 1, 1958, the National Assembly approved the composition of the government headed by G. On the instructions and with the participation of G., a new constitution of the republic was prepared (September 1958), which narrowed the powers of the parliament and significantly expanded the rights of the president. On December 21, 1958, he was elected President of the French Republic. On December 19, 1965, he was re-elected to the presidency for a new 7-year term. France's foreign policy concept was distinguished by its desire to ensure France's independence in decision-making on the most important issues of European and world politics. One of the most significant steps in this regard was France’s withdrawal from the NATO military organization in 1966. Germany’s foreign policy was characterized by a realistic approach to a number of major international problems (a statement recognizing the final nature of the post-war German borders, 1959; condemnation of US aggression in Vietnam; condemnation of Israeli attacks on Arab states, etc.). At the same time, while continuing to implement plans to create its own nuclear forces, France did not sign the Triple Nuclear Test Ban Treaty (1963). France did not sign the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (1968), however, declaring at the UN that it would behave in this area in the same way as the states that acceded to this Treaty on April 28, 1969, after the defeat in the referendum on April 27 ( on the issue of the reorganization of the Senate and the reform of the territorial-administrative structure of France), reflecting the dissatisfaction of a certain part of the French population with government policies, G. resigned from the post of president. During the years of G.'s tenure as president, Soviet-French relations received significant development. In 1966, G. paid an official visit to the USSR; As a result of negotiations and the signing of the Soviet-French Declaration on June 30, 1966, an important stage in the history of Soviet-French relations was opened.

Works: Une mauvaise rencontre, P., 1916; Histoire des troupes du Levant, P., 1921; La discorde chez l "ennemi, 2 ed., P., 1944; Le fil de l-epee, P., 1946; La France sera la France, P., 1952; La France et son armee, P., 1965; Discours et messages, t. 1-5 Memoires de guerre, , P., 1968-69; Meemoires d'espoir, t. 1-2, P., 1970-71; in Russian lane - Professional Army, M., 1935; Military memoirs, vol. 1-2, M., 1957-1960.

Biography (M. Ts. Arzakanyan)

Charles de Gaulle (Gaulle) (1890-1970) - French politician and statesman, founder and first president (1959-1969) of the Fifth Republic. In 1940, he founded the patriotic movement “Free France” (from 1942 “Fighting France”) in London, which joined the anti-Hitler coalition; in 1941 he became the head of the French National Committee, in 1943 - the French Committee for National Liberation, created in Algeria. From 1944 to January 1946, de Gaulle was the head of the French Provisional Government. After the war, he was the founder and leader of the Rally of the French People party. In 1958, Prime Minister of France. On de Gaulle's initiative, a new constitution was prepared (1958), which expanded the rights of the president. During his presidency, France implemented plans to create its own nuclear forces and withdrew from the NATO military organization; Soviet-French cooperation received significant development.

Origin. Formation of worldview

Charles De Gaulle was born on November 22, 1890, in Lille, into an aristocratic family and was brought up in the spirit of patriotism and Catholicism. In 1912, he graduated from the Saint-Cyr military school, becoming a professional soldier. He fought on the fields of the First World War 1914-1918, was captured, and was released in 1918.

De Gaulle's worldview was influenced by such contemporaries as philosophers Henri Bergson and Emile Boutroux, writer Maurice Barrès, and poet and publicist Charles Péguy.

Even during the interwar period, Charles became a supporter of French nationalism and a supporter of a strong executive. This is confirmed by the books published by de Gaulle in the 1920-1930s - “Discord in the Land of the Enemy” (1924), “On the Edge of the Sword” (1932), “For a Professional Army” (1934), “France and Its Army” (1938). In these works devoted to military problems, de Gaulle was essentially the first in France to predict the decisive role of tank forces in a future war.

The Second World War

The Second World War, at the beginning of which Charles de Gaulle received the rank of general, turned his whole life upside down. He decisively refused the truce concluded by Marshal Henri Philippe Pétain with Nazi Germany and flew to England to organize the struggle for the liberation of France. On June 18, 1940, de Gaulle spoke on London radio with an appeal to his compatriots, in which he urged them not to lay down their arms and to join the Free France association he founded in exile (after 1942, Fighting France).

At the first stage of the war, de Gaulle directed his main efforts towards establishing control over the French colonies, which were under the rule of the pro-fascist Vichy government. As a result, Chad, Congo, Ubangi-Chari, Gabon, Cameroon, and later other colonies joined the Free French. Free French officers and soldiers constantly took part in Allied military operations. De Gaulle sought to build relations with England, the USA and the USSR on the basis of equality and upholding the national interests of France. After the landing of Anglo-American troops in North Africa in June 1943, the French Committee for National Liberation (FCNL) was created in the city of Algiers. Charles De Gaulle was appointed its co-chairman (along with General Henri Giraud), and then its sole chairman.

In June 1944, the FCNO was renamed the Provisional Government of the French Republic. De Gaulle became its first head. Under his leadership, the government restored democratic freedoms in France and carried out socio-economic reforms. In January 1946, de Gaulle left the post of prime minister, disagreeing on major domestic political issues with representatives of the left parties of France.

Charles de Gaulle during the Fourth Republic

That same year, the Fourth Republic was established in France. According to the 1946 Constitution, real power in the country belonged not to the president of the republic (as de Gaulle proposed), but to the National Assembly. In 1947, de Gaulle again became involved in the political life of France. He founded the Rally of the French People (RPF). The main goal of the RPF was to fight for the abolition of the 1946 Constitution and the conquest of power through parliamentary means to establish a new political regime in the spirit of de Gaulle’s ideas. The RPF was initially a great success. 1 million people joined its ranks. But the Gaullists failed to achieve their goal. In 1953, de Gaulle dissolved the RPF and withdrew from political activities. During this period, Gaullism finally took shape as an ideological and political movement (ideas of the state and “national greatness” of France, social policy).

Fifth Republic

The Algerian crisis of 1958 (Algeria's struggle for independence) paved the way for de Gaulle to power. Under his direct leadership, the 1958 Constitution was developed, which significantly expanded the prerogatives of the country's president (executive branch) at the expense of parliament. This is how the Fifth Republic, which still exists today, began its history. Charles de Gaulle was elected its first president for a seven-year term. The priority task of the president and government was to resolve the “Algerian problem.”

De Gaulle firmly pursued a course towards Algerian self-determination, despite serious opposition (rebellions of the French army and ultra-colonialists in 1960-1961, terrorist activities of the OAS, a number of assassination attempts on de Gaulle). Algeria was granted independence with the signing of the Evian Accords in April 1962. In October of the same year, the most important amendment to the 1958 Constitution was adopted in a general referendum - on the election of the president of the republic by universal suffrage. On its basis, in 1965, de Gaulle was re-elected president for a new seven-year term.

Charles de Gaulle sought to implement his foreign policy in line with his idea of the “national greatness” of France. He insisted on equal rights for France, the United States and Great Britain within NATO. Having failed to achieve success, the president withdrew France from the NATO military organization in 1966. In relations with Germany, de Gaulle managed to achieve noticeable results. In 1963, a Franco-German cooperation agreement was signed. De Gaulle was one of the first to put forward the idea of a “united Europe”. He thought of it as a “Europe of fatherlands,” in which each country would retain its political independence and national identity. De Gaulle was a supporter of the idea of détente. He set his country on the path of cooperation with the USSR, China and third world countries.

Charles de Gaulle paid less attention to domestic policy than to foreign policy. The student unrest in May 1968 indicated a serious crisis engulfing French society. Soon the president put forward a project on a new administrative division of France and Senate reform to a general referendum. However, the project did not receive the approval of the majority of the French. In April 1969, de Gaulle voluntarily resigned, finally abandoning political activity.

How General de Gaulle defeated America

In 1965, General Charles de Gaulle flew to the United States and, at a meeting with American President Lyndon Johnson, announced that he intended to exchange 1.5 billion paper dollars for gold at the official rate of $35 per ounce. Johnson was informed that a French ship loaded with dollars was in the New York port, and a French plane had landed at the airport with the same cargo on board. Johnson promised the French president serious problems. De Gaulle responded by announcing the evacuation of NATO headquarters, 29 NATO and US military bases from French territory and the withdrawal of 33 thousand alliance troops.

Ultimately, both were done.

Over the next 2 years, France managed to buy more than 3 thousand tons of gold from the United States in exchange for dollars.

What happened to those dollars and gold?

De Gaulle is said to have been very impressed by an anecdote told to him by the former Minister of Finance in the Clemenceau government. At an auction for a painting by Raphael, an Arab offers oil, a Russian offers gold, and an American takes out a wad of banknotes and buys it for 10 thousand dollars. In response to de Gaulle's perplexed question, the minister explains to him that the American bought the painting for only 3 dollars, because... The cost of printing one $100 bill is 3 cents. And de Gaulle unequivocally and definitively believed in gold and only gold. In 1965, de Gaulle decided that he did not need these pieces of paper.

De Gaulle's victory was Pyrrhic. He himself lost his post. And the dollar took the place of gold in the global monetary system. Just a dollar. Without any gold content.

Biography

Charles de Gaulle (Gaulle) (November 22, 1890, Lille - November 9, 1970, Colombe-les-deux-Eglises), French politician and statesman, founder and first president of the Fifth Republic.

Origin. Formation of worldview.

De Gaulle was born into an aristocratic family and raised in the spirit of patriotism and Catholicism. In 1912 he graduated from the Saint-Cyr military school, becoming a professional military man. He fought on the fields of the First World War 1914-1918, was captured, and was released in 1918. De Gaulle's worldview was influenced by such contemporaries as the philosophers A. Bergson and E. Boutroux, the writer M. Barres, and the poet C. Peguy. Even during the interwar period, he became a supporter of French nationalism and a supporter of a strong executive power. This is confirmed by the books published by de Gaulle in the 1920-30s - “Discord in the Land of the Enemy” (1924), “On the Edge of the Sword” (1932), “For a Professional Army” (1934), “France and Its Army” (1938). In these works devoted to military problems, de Gaulle was essentially the first in France to predict the decisive role of tank forces in a future war.

The Second World War.

The Second World War, at the beginning of which de Gaulle received the rank of general, turned his whole life upside down. He resolutely refused the truce concluded by Marshal A.F. Pétain with Nazi Germany and flew to England to organize the struggle for the liberation of France. On June 18, 1940, de Gaulle spoke on London radio with an appeal to his compatriots, in which he urged them not to lay down their arms and to join the Free France association he founded in exile (after 1942, Fighting France). At the first stage of the war, de Gaulle directed his main efforts towards establishing control over the French colonies, which were under the rule of the pro-fascist Vichy government. As a result, Chad, Congo, Ubangi-Shari, Gabon, Cameroon, and later other colonies joined the Free France. Free French officers and soldiers constantly took part in Allied military operations. De Gaulle sought to build relations with England, the USA and the USSR on the basis of equality and upholding the national interests of France. After the landing of Anglo-American troops in North Africa in June 1943, the French Committee for National Liberation (FCNL) was created in the city of Algiers. De Gaulle was appointed its co-chairman (along with General A. Giraud), and then its sole chairman. In June 1944, the FCNO was renamed the Provisional Government of the French Republic. De Gaulle became its first head. Under his leadership, the government restored democratic freedoms in France and carried out socio-economic reforms. In January 1946, de Gaulle left the post of prime minister, disagreeing on major domestic political issues with representatives of the left parties of France.

During the Fourth Republic.

That same year, the Fourth Republic was established in France. According to the 1946 Constitution, real power in the country belonged not to the president of the republic (as de Gaulle proposed), but to the National Assembly. In 1947, de Gaulle again became involved in the political life of France. He founded the Rally of the French People (RPF). The main goal of the RPF was to fight for the abolition of the 1946 Constitution and the conquest of power through parliamentary means to establish a new political regime in the spirit of de Gaulle’s ideas. The RPF was initially a great success. 1 million people joined its ranks. But the Gaullists failed to achieve their goal. In 1953, de Gaulle dissolved the RPF and withdrew from political activities. During this period, Gaullism finally took shape as an ideological and political movement (ideas of the state and “national greatness” of France, social policy).

Fifth Republic.

The Algerian crisis of 1958 (Algeria's struggle for independence) paved the way for de Gaulle to power. Under his direct leadership, the 1958 Constitution was developed, which significantly expanded the prerogatives of the country's president (executive branch) at the expense of parliament. This is how the Fifth Republic, which still exists today, began its history. De Gaulle was elected its first president for a seven-year term. The priority task of the president and government was to resolve the “Algerian problem.” De Gaulle firmly pursued a course towards self-determination in Algeria, despite serious opposition (rebellions of the French army and ultra-colonialists in 1960-1961, terrorist activities of the OAS, a number of assassination attempts on de Gaulle). Algeria was granted independence with the signing of the Evian Accords in April 1962. In October of the same year, the most important amendment to the 1958 Constitution was adopted in a general referendum - on the election of the president of the republic by universal suffrage. On its basis, in 1965, de Gaulle was re-elected president for a new seven-year term. De Gaulle sought to pursue foreign policy in line with his idea of the “national greatness” of France. He insisted on equal rights for France, the United States and Great Britain within NATO. Unable to achieve success, the president withdrew France from the NATO military organization in 1966. In relations with Germany, de Gaulle managed to achieve noticeable results. In 1963, a Franco-German cooperation agreement was signed. De Gaulle was one of the first to put forward the idea of a “united Europe”. He thought of it as a “Europe of fatherlands,” in which each country would retain its political independence and national identity. De Gaulle was a supporter of the idea of détente. He set his country on the path of cooperation with the USSR, China and third world countries. De Gaulle paid less attention to domestic policy than to foreign policy. The student unrest in May 1968 indicated a serious crisis engulfing French society. Soon the president put forward a project on a new administrative division of France and Senate reform to a general referendum. However, the project did not receive the approval of the majority of the French. In April 1969, de Gaulle voluntarily resigned, finally abandoning political activity.

Features of the political course of Charles de Gaulle (Course work)

Introduction

The history of modern France is inextricably linked with the name of Charles de Gaulle, an outstanding military, political and statesman. His influence on the course of socio-political development of France and all of Europe as a whole is so great that it cannot be compared. Charles de Gaulle made a great contribution to the history of the French state and international relations in the twentieth century. This explains the relevance of the topic of this course work.

They began to write about the President of the V Republic during his lifetime. In Russia, the first biography of de Gaulle was published by Vera Ivanovna Antyukhina-Moskvichenko. In the last two decades, the volume of data on Charles de Gaulle has increased dramatically.

When writing this work, a complex of sources was used, in particular the works of Charles de Gaulle himself, where the president describes and analyzes his activities, and literature. Literature can be divided into the following groups: reference and encyclopedic literature, educational literature, periodicals, monographs. From the monograph, one can highlight Marina Arzakanyan’s book “De Gaulle”. This book is the most complete biography of Charles de Gaulle, which describes all the details of his life, studies, participation in the First and Second World Wars and political activities.

The purpose of this work is to identify the peculiarities of the political course of Charles de Gaulle.

In accordance with the following tasks:

* consider the categorical and conceptual apparatus on the topic of the course work;

* characterize the conditions for the formation of Charles de Gaulle as a politician;

* analyze the internal politics of France;

* determine the position of France in the system of international relations.

To study this topic, methods of system analysis, systematization, and comparative analysis were used. Using these methods, all the material considered on the topic of the course work was systematized and analyzed, the features of the domestic and foreign policy of France during the reign of Charles de Gaulle were identified.

The presented course work consists of two chapters. The first chapter is a theoretical part, which reveals the basic concepts of politics and gives a brief overview of the biography of General de Gaulle. The second chapter is a practical part. It is dedicated to the activities of Charles de Gaulle in the political sphere.

Chapter 1. Personality in the context of political activity

1 Policy: definition and approaches

Within the framework of the topic of this course work, the main directions of the domestic and foreign policy of France during the reign of Charles de Gaulle will be considered. In order to better navigate this topic, it is necessary to characterize the basic concepts of political science.

There are many definitions of the concept "policy". From the point of view of anthropology, politics is a form of civilized communication between people based on law, a way of collective human existence. From a systemic point of view, politics is a relatively independent system, a complex social organism, an integrity limited from the environment and in continuous interaction with it.1

In general, this phenomenon can be given the following definition: politics is the activity of individuals and social groups associated with relationships regarding the conquest, retention and use of power in order to realize their interests. Depending on the scale and level of policy implementation, foreign and domestic policies are distinguished.2

Domestic policy is a set of activities of the state, its structures and institutions for the organizational, concrete and substantive expression of the interests of the people 1) 1890 - 1940. - raising Charles in the family, receiving an education, participating in the First World War.

1940 - 1958 - Charles de Gaulle's participation in World War II and the beginning of his political career.

1958 - 1970 - Charles de Gaulle - President of the V Republic.

When considering the main stages of Charles de Gaulle's life, special attention will be paid to how de Gaulle came into politics.

De Gaulle was born in 1890 in Lille. His parents, Jeanne and Henri de Gaulle, a nobleman and a devout Catholic, had only five children. Charles spent his childhood in a large apartment near Rue Vaugirard on the left bank of the Seine. Mother and father attached great importance to the patriotic education of children; they were taught discipline from a very early age. During his childhood games, Charles already imagined himself as a commander and always played only for the French.1 Why exactly for the French is easy to guess. The spirit of patriotism and love for France reigned in the family, which later influenced de Gaulle’s fate and choice of a military career.

In 1896, Charles entered the elementary school of St. Thomas Aquinas, and in 1900, the Jesuit College of the Immaculate Conception. Proud and obstinate, Charles was at the same time a romantically minded young man who knew how to admire and think deeply about the future of his homeland.1 Much attention at the college is paid to religious disciplines, education and ancient heritage. The Jesuits took the teaching of French language and literature, history, geography, mathematics, and German very seriously. Little de Gaulle immediately fell in love with history, and he was especially interested in the past of his native country. Poetry becomes Charles's real passion in adolescence. While no one is at home, he reads, thinks, writes, and not only poetry. At the age of 14, Charles writes a short story, “The German Campaign,” in which he imagines himself as the commander of French troops fighting against Germany.2

Charles de Gaulle grew up as a true patriot, interested in the past of his country and thinking about its future. It is not surprising that when the time came to choose a profession, Charles de Gaulle decided to become a military man.

At the end of the summer of 1907, Charles and his brother Jacques left for the small Belgian town of Antoine, where he entered the Jesuit college Sacré-Coeur. The following summer, seventeen-year-old Charles makes his first trip abroad with the Jesuit fathers - to Germany and Switzerland. At the beginning of autumn, he returns to Paris in a good mood and firmly decides to enter the Saint-Cyr military school, since he believes that “the army occupies a very large place in the life of peoples.”3

In the fall of 1909, eighteen-year-old Charles de Gaulle successfully passed his exams and became a cadet at a military school. The first important step towards achieving the great goal of becoming a military man has been taken. According to the existing order, before studying, all enlisted people must first spend a year in any branch of the active army, where they were trained in military affairs and accustomed to strict routines and discipline. Charles chooses infantry and goes to the city of Arras.

In October 1910, the young de Gaulle, with the rank of corporal, crossed the threshold of the famous military school, where he brilliantly completed his studies in 1912 and graduated with the rank of junior lieutenant with excellent certification. While studying in Saint-Cyr, de Gaulle was independent, but always responsive and friendly. He was distinguished by his straight posture and tall stature. The students tried to follow the motto of Saint-Cyr - “Learn to win!” The school adopted the following daily routine: wake up at five thirty, breakfast at six, physical training classes took place from seven to nine - gymnastics, fencing, horse riding. Then, until noon, the pupils attended lessons on law, history, geography, and French literature. The afternoon was devoted exclusively to military affairs. This daily routine required concentration, discipline, and great dedication from the students. Charles de Gaulle immediately showed himself to be a man who was not afraid of any difficulties. The school teachers praised de Gaulle:

* "Behavior - impeccable

* Abilities - bright

* Character - straight

* Diligence is great"

Upon graduation from college, Charles de Gaulle became an officer and came under the command of Colonel Philippe Petain. In the fall of 1913, de Gaulle became a lieutenant and continued to serve in Arras. In August 1914, the First World War began. Charles de Gaulle went through all the harsh everyday life of this war. In 1916, the largest battle took place on the Western Front in the area of the city of Verdun. The regiment in which de Gaulle served and was battalion commander immediately went on the offensive. The battalion was almost completely destroyed, and de Gaulle was seriously wounded, from which he lost consciousness and was considered dead. In fact, Charles de Gaulle survived. He was captured, from which he tried to escape five times, and all attempts ended in failure. De Gaulle was released only in 1918 after the signing of an armistice with Germany. It is easy to imagine what Charles de Gaulle's state of mind was like. Losing a battle, being captured and not being able to escape from there was humiliating and unacceptable.

It is difficult to recover from such a defeat. Therefore, de Gaulle was thinking about saying goodbye to his military career forever. However, by nature, de Gaulle was an ambitious and purposeful person; he was not used to retreating from his intended goal. And Charles’s relatives convinced him that he should continue his military career. That's why he didn't leave the army. At the beginning of 1919, he was sent for an internship to the Saint-Mexican military school, where he served.

Soon Charles de Gaulle married the daughter of an industrialist, Yvonne, whom he was introduced to by a friend of his mother. He spent his honeymoon with his young wife in Italy. In 1921, Yvonne gave birth to a boy. After the birth of his child, de Gaulle decided to temporarily change his occupation and got a job as a history teacher in Saint-Cyr and at the same time did an internship in different troops. History attracted the future president from childhood; in addition, his father was a historian, however, he could not completely give up his military career.

In November 1922, Charles de Gaulle became a student at the Higher Military School. His goal was to achieve significant success in military activities, and he gradually, step by step moved towards it.1

In September 1924, de Gaulle was appointed to the general headquarters of the French army in the Rhineland and left for Mainz. He received a promotion only in 1927. During his military service, Charles did not stop writing. He writes articles on military topics for periodicals and monitors the situation on the Rhine. Meanwhile, France soon disbanded all the regiments that occupied the Rhine, and de Gaulle was sent to Lebanon.2

In 1931, Charles de Gaulle returned to Paris and was appointed secretary of the Supreme Council of National Defense. In 1933, de Gaulle received the rank of lieutenant colonel. From this moment a new stage of his military career begins. He was given the task of developing the text of a law on the organization of public services in peace and war. There are several reasons why this task was entrusted to de Gaulle. Firstly, he has proven himself well as a military man. Secondly, de Gaulle took part in more than one war and had extensive experience in organizational and military activities. Charles de Gaulle took up the matter in the most serious manner.

When developing this law, Charles de Gaulle opposed a defensive strategy, citing the fact that it could lead to irreparable consequences. He wrote the articles “Let’s Create a Professional Army” and “How to Create a Professional Army.” In 1934, his main work was published - the book “For a Professional Army”, in which de Gaulle declares the need to create a professional army capable of withstanding any enemy attacks. The publication of this book did not live up to de Gaulle's hopes, but it attracted attention in Germany. The lieutenant colonel put forward his own military doctrine, but it did not find a response among the highest military ranks. Then de Gaulle realized that in order to implement his ideas it was necessary to enlist the support of influential politicians.

At the end of 1934, de Gaulle's friend Jean Auburtin introduced him to the right-wing politician Paul Reynaud. Paul Reynaud was inspired by de Gaulle's idea of creating mechanized army units and decided to promote its implementation.

Having created a new cabinet, Paul Reynaud appointed de Gaulle Deputy Minister of War. One of Charles de Gaulle's most important tasks was to meet with British Prime Minister Winston Churchill and obtain military assistance from him. De Gaulle successfully fulfills this task.1

During World War II, the colonel did not leave military activities. De Gaulle was appointed commander of the tank forces of the 5th Army. His division, at the cost of incredible efforts, managed to stop the enemy near Alsace.

During this period, de Gaulle not only advanced far up the military career ladder, but also managed to get into the political elite; he takes part in the management and organization of the country's military forces. The following qualities helped him in this: determination, ambition, hard work, connections.

De Gaulle's formation as a politician began with his upbringing in the family. Charles's parents early instilled in Charles a love of France and raised him in the spirit of patriotism, which affected de Gaulle's interest in the fate of his country. It is therefore not surprising that Charles de Gaulle's favorite subject was history, which allowed him not only to learn about France's past, but also to reflect on its future.

The final formation of the personal qualities of the future politician occurred in the process of receiving military education and developing a career in this field. The strict daily routine that was present at the military school taught de Gaulle discipline and taught him how to rationally organize his activities. Constantly being in a team contributed to the development of communication skills in the future politician. Participation in hostilities, including the experience of being in captivity, strengthened character, taught us to deal with difficulties and hardships and not to deviate from the intended goal.

Having taken a managerial position, de Gaulle manifests himself as an army reformer. Having analyzed the weaknesses of the French military structure, he proposes projects for its modernization. However, without receiving support from the government, de Gaulle sets the goal of becoming a politician to implement his ideas. De Gaulle's main aspiration was to stabilize the internal system of the state and increase the country's role in the international arena.

Chapter 2. The concept of political activity of Charles de Gaulle

1 De Gaulle's domestic policy

Charles de Gaulle's political activities extended to the domestic and foreign policies of France. This paragraph presents the development of the internal politics of the Fifth Republic.

De Gaulle devoted his main attention to the development of a new Constitution for France. According to the Constitution of the IV Republic, the president, elected by parliament for a term of seven years, had a limited sphere of competence; he was rather invested with the appearance of power, since he could influence the adoption of laws only in individual cases. In general, all power was assigned to parliament. De Gaulle sought to completely change the established order. He entrusted the drafting of the project to a group of high-ranking officials - members of the State Council, led by Debre. The State Council began its work on June 12. The draft being developed was discussed in parts by the Government Committee, headed by General de Gaulle himself. The Constitutional Advisory Committee met for about half a month. By the end of July, the draft Constitution was drawn up.

On September 1, 1958, the third post-liberation referendum on constitutional issues was held in France. In October of the same year, a new French constitution came into force, establishing a new political order in the country.

According to this document, the powers of the president were significantly expanded. He received the right:

* appoint the prime minister and individual ministers;

* return bills adopted by Parliament for re-discussion;

* submit to a referendum, at the proposal of the government or both chambers, any bill concerning the organization of state power or the approval of international agreements that could affect the activities of state institutions;

* dissolve the National Assembly and call new elections.1

Legislative power belonged to parliament, consisting of two chambers. The first chamber - the National Assembly - was elected by direct universal suffrage for a term of five years. It passes laws governing the exercise of civil rights, the judicial system, the tax system, elections, the status of civil servants and nationalization. In such important areas as defense, organization and revenue of local governments, education, labor law, and the status of trade unions, the National Assembly should determine only “general principles.” All other issues are resolved by the government and administration in the exercise of administrative power. The second chamber, with the right of “delaying veto” - the Senate, was elected by indirect voting, renewed every three years by one third. The National Assembly, like the Senate, could neither control nor remove the president. It could only achieve the resignation of the government.2 Article 16 of the 1958 Constitution gave the right to the president of the republic in emergency circumstances to take full power into his own hands.3

Charles de Gaulle drafted the new Constitution in such a way that almost all power was in the hands of the president, and none of the elected chambers could influence the adoption of a particular decision. That is, in fact, the Constitution legally formalized the regime of personal power of the president.

Believing that the new Constitution would lead to a dangerous expansion of executive power and threaten democratic freedoms, the Communist Party called for a vote against it. The draft Constitution was also criticized by some socialists, left-wing radicals and groups close to them, whose leaders were Pierre Mendès-France and François Miterrand. However, all other political parties, including the official leadership of the Socialist Party, approved the government bill. During the referendum, 79% of voters voted for the draft Constitution. He was supported not only by the right, but also by many left-wing voters who were disillusioned with the political system and practical activities of the Fourth Republic. Between a third and a half of voters who supported the draft Constitution believed that if it were rejected and de Gaulle resigned, civil war would break out in France.

De Gaulle's personal authority was of great importance. Many French, who remembered his role in the Resistance movement and his struggle against the “European army,” believed that only de Gaulle could adequately defend national interests and achieve peace in Algeria.

Thus, de Gaulle was supported by a broad coalition of various class forces, whose participants were often guided by opposing goals. The adoption of the constitution legally formalized the creation of the Fifth Republic. In December 1958, de Gaulle was elected president of France.

Within the framework of domestic policy, the president devoted an important place to increasing the economic efficiency of French industry and its modernization. He attached particular importance to state plans, the implementation of which he called the “ardent duty” of the French. The plan consisted of three elements, closely related to each other. The first element is a real end to inflation. The cure for inflation was initially to reduce government spending while increasing revenues, with the goal of stopping the waste of national income and increasing savings. In this regard, it was proposed to limit wages and salaries in the public sector to a “fixed” four percent increase; reduce government subsidies to cover the deficit of nationalized enterprises and the social insurance system, reduce subsidies to food producers, and at the same time increase taxes on joint-stock companies and on high-income earners. The second series of measures related to currency. The goal was to establish the franc "on a sound basis" and increase the competitiveness of national goods in the common market. The third set of measures was aimed at liberalizing foreign trade exchanges.1

A whole system of government loans, subsidies and other financial and economic measures outlined in the Third (1958-1961) and Fourth (1961-1965) economic and social development plans contributed to the accelerated development of leading industries such as science and technology. De Gaulle's policy included turning France into a prosperous industrial power.2

In 1958, the fifteenth (since 1926) devaluation of the franc was carried out, which stimulated French exports. Since January 1, 1960 The government introduced a new monetary unit - the “heavy” franc, the value of which was a hundred times higher than the value of the old, “light” franc. The strength of the franc was proclaimed not only in France, but also recognized abroad. The franc became convertible and could be exchanged for any hard currency. In addition, new coins and banknotes were issued (one new franc per hundred old).1

In 1959 and 1961, regulations were issued on the “interest” of workers in the results of the enterprise. Entrepreneurs were encouraged to allocate a small portion of their profits to reward workers (in the form of additional bonuses or special “worker shares”). However, most entrepreneurs rejected this proposal.

Much attention was paid by the government to the development of culture. The budget of the Ministry of Culture, which was headed by the famous writer and resistance participant A. Malraux, increased 3 times faster than the budgets of other ministries. Malraux launched a broad campaign to protect and disseminate cultural heritage: the construction of museums, libraries, houses for youth and culture. Restoration of historical monuments has begun. Masterpieces of French architecture - the Louvre, Notre Dame Cathedral, the Palace of Justice, the Pantheon, the Arc de Triomphe - have again regained their pristine white color.

French cinema was booming. French directors of the “new wave” - Francois Truffaut, Claude Chabrol and others - won worldwide recognition. They updated the themes and style of cinema, abandoned pompous commercial films, turned to the everyday life of people, especially young people, and criticized modern society and traditional social values.

Having analyzed the main actions of the government led by de Gaulle in the field of domestic policy, we can highlight the following priorities of its concepts in this area:

* normalization of the internal situation in France, strengthening the political role of the president,

* concentration of all power in the hands of the president,

* increasing the competitiveness of the economy,

* modernization of social policy and development of culture.

A set of these measures made it possible to stabilize the position of the French Republic after World War II.

2 De Gaulle's foreign policy

Charles de Gaulle's main attention was given to the field of foreign policy. In this area, a number of directions can be distinguished: colonial (Algerian), North American (relations with the USA, Great Britain), European (relations with Germany, ECSC countries), Franco-Soviet direction.

A dangerous situation that required immediate government intervention arose in Algeria. The President was a supporter of the independence of the colony. He was convinced that France could not follow any other path, and considered it pointless to keep Algeria by force under French sovereignty. However, not all members of the government shared his point of view: Algeria split the French in two. Some of the French sympathized with the Algerian Europeans and believed that the metropolis was obliged to protect their interests. Others believed that France, suffering huge losses in the colonial war, should leave these overseas departments.1 On June 4, 1958, Charles de Gaulle flew to Algeria. He firmly pursued a course towards Algerian self-determination, despite serious opposition (rebellions of the French army and supporters of maintaining colonial dependence on France in 1960-1961, terrorist activities of the OAS, a number of assassination attempts on de Gaulle).2

Upon his arrival in Algiers, de Gaulle addressed a large crowd of French and Algerians. He said: “I know what happened here. I know what you wanted to do. I see that the road that you opened in Algeria is the path of renewal and brotherhood. I say renewal in all respects, including ours.” institutions. I declare: from today, France considers that in all of Algeria there is only one category of inhabitants - full-fledged Frenchmen with the same rights and duties."1

In April 1962, the Evian Agreements were signed, according to which Algeria was granted independence.2 The new French constitution introduced a separate section regulating the status of French colonies. It proclaimed the creation of a “Community consisting of the French Republic and all its overseas territories.” One of the articles in this section stated that all "overseas departments" of France could retain their status as part of the republic, as well as "form separate states" if their territorial assemblies express their will no later than four months after adoption of the constitution.3 Algeria became “French,” which the ultra-colonialists had been waiting for from the president for a very long time.

The next component of de Gaulle's foreign policy was the elimination of France's dependence on the "senior partners" in the North Atlantic Pact - the USA and England. In 1959, the president removed the French fleet based in the Mediterranean from NATO control and prohibited the deployment of American nuclear missile weapons on French territory. Believing that only the possession of its own nuclear weapons could guarantee the "greatness of the nation", de Gaulle's government made enormous and expensive efforts to create a nuclear strike force. In February 1960, having exploded its first atomic bomb at one of the French test sites in the Sahara, France entered the “club of atomic powers” along with the USSR, the USA and Great Britain. However, while continuing to implement plans to create its own nuclear forces, France did not sign the Triple Nuclear Test Ban Treaty (1963). France did not sign the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (1968), however, declaring at the UN that it would behave in this area in the same way as the states that acceded to this Treaty.1

De Gaulle was not opposed to the idea of détente; he understood the importance of cooperation in the international sphere. Therefore, the most important direction of his foreign policy was rapprochement with Germany. In September 1958 De Gaulle's first meeting took place with German Chancellor Karl Adenauer, during which both leaders announced their desire to “put an end to the previous hostility forever.” In January 1963, in Paris, they signed an agreement on cooperation in the fields of foreign policy, defense, education and youth education. They decided to consult with each other regularly.

France's European policy has changed significantly. Having condemned the plans for the military-political “integration of Europe,” de Gaulle contrasted them with the idea of a “Europe of states” - an interstate union in which all its members would retain their national sovereignty. The French government opposed England's admission to the Common Market, believing that the British government was too closely connected with the United States and could become a conductor of American influence in Europe. By the end of the 50s. Relations between the ECSC countries began to improve, and France became involved in the further development of integration processes in Europe. In 1959, France implemented the 1957 Treaty of Rome on the Common Market. Economic cooperation began to develop between the EEC countries.

In the Middle East, France, while maintaining ties with Israel, decided to pursue a policy of “friendship and cooperation” towards the Arab countries, where about 100 million people lived and 70% of the world’s oil reserves were located. In June 1967, after the start of Israel's "six-day war against the Arab states", the French government acceded to the UN Security Council resolution demanding the withdrawal of Israeli troops from the occupied territories.1

France's relations with the Soviet Union and other socialist countries improved significantly. In 1960, at the invitation of President de Gaulle, the head of the Soviet government N.S. visited France for the first time. Khrushchev. As a result of his trip, the USSR and France agreed to expand trade and cultural ties with each other. Agreements were concluded on scientific cooperation, including the peaceful use of atomic energy. In 1966, President de Gaulle made a return visit to the USSR. It ended with the adoption of a joint declaration, which proclaimed the desire of the USSR and France to establish an “atmosphere of detente” between East and West. France and the Soviet Union agreed to hold regular political consultations with the aim of developing Franco-Soviet relations "from agreement to cooperation."

In the field of foreign policy, Charles de Gaulle took a number of actions to increase the role of France in the international arena. France became an independent strong power. De Gaulle brought the country out of subordination to the United States and England and established relations with European countries and the Soviet Union. This contributed to the development of the country's economy. Thanks to the efforts of Charles de Gaulle, France became one of the great powers.

Conclusion

The reign of Charles de Gaulle was called "Gaullism". Now “Gaullism” is a political ideology based on the ideas and actions of General de Gaulle.

The main idea of "Gaullism" is the independence of France from any other states, giving it the status of great. Charles de Gaulle managed to bring French policy out of the subordination of such great powers as the USA and England. Charles de Gaulle established relations with a number of European countries, primarily with Germany and the Soviet Union, which helped not only the development of the country itself and its economy, but also made a great contribution to the development of international relations.

During his entire tenure as president, de Gaulle managed to make a number of internal political changes in the country. A new version of the Constitution was published, the text of which granted full power to the president. The economic sphere and social policy received further development. The government's actions led to the stabilization of the country's internal situation and economic recovery after World War II. Fiscal measures strengthened the French currency, making it more competitive. In addition, the president paid attention to the preservation of cultural values and support for art. All cultural monuments destroyed after the war were restored and acquired their original appearance.

Being a talented theorist, Charles de Gaulle twice successfully ruled the country and twice managed to bring it out of a deep crisis, thanks to his ability to competently organize the activities of the structure entrusted to him. After resigning as president, Charles de Gaulle left the country “on the rise.”

List of sources and literature used

Sources

* 1. Statements of Charles de Gaulle [Electronic resource] - #"justify">Appendix No. 1

* 2. Charles de Gaulle - “the greatest of the French.”

Appendix No. 2

Quotes by Charles de Gaulle.

* "You will live, only the best are killed."

* “When I’m right, I usually get angry. And Churchill gets angry when he’s wrong. So it turned out that we were very often angry with each other.”

* “I respect only those who fight with me, but I do not intend to tolerate them.”

* "The minister should not complain about newspapers or even read them. He should write them."

* “Always choose the most difficult path - you will not meet competitors on it.”

* "You can be sure that Americans will do every stupid thing they can think of, plus a few more that are unimaginable."

* "Me or chaos."

* "France is only truly France if it stands in the forefront... France, devoid of greatness, ceases to be France"

Biography

Like all great statesmen, Charles de Gaulle has been preserved in people's memory in a very contradictory manner. Sometimes it seems that when talking about him, they are talking about completely different people. Regardless of subjective opinions, he is the founding father of the modern French state, proudly calling itself the Fifth Republic. In the 42 years since his death, the political husks have fallen away from the image of this man, and it has become clear that this military general saw the future better than most of his contemporaries.

Biography

He was born in the century before last, in 1890 in Lille, and since childhood he dreamed of achievements for the glory of France, so, quite logically, he chose a military career. He graduated from the military school in Saint-Cyr. He experienced his baptism of fire on the fronts of the First World War, was seriously wounded, counted among the dead, and was captured. I regularly tried to escape. He was imprisoned in a fortress, where he met the Russian lieutenant Mikhail Tukhachevsky. He eventually fled, but de Gaulle did not succeed. He was released only after the defeat of Germany, but did not go home, but remained in Poland as an instructor. There he had to take part in repelling the attack of the Red Army, which was led by his acquaintance Tukhachevsky.

De Gaulle regarded the behavior of Marshal Pétain, who surrendered France to the Germans, as betrayal. From this moment, the new life of General Charles de Gaulle, the leader of the struggle for the liberation of the Motherland from the occupiers, begins. The enormous moral authority acquired in this role was the reason that at the end of the war France was among the victors of Nazism. The struggle was not only military, but also political, and thus forged a public figure who rallied the French (often against their will) in order to bring France into the first rank of world powers.

Although he had been the head of the French Provisional Government since 1944, he left it after the adoption of the constitution of the Fourth Republic in 1946 due to disagreements with left-wing politicians. To him, a staunch supporter of strong centralized power, it seemed disastrous to give power in the country to a collective body - the National Assembly. Time has shown that he was right. When the Algerian crisis arrived in 1958, Charles de Gaulle returned to politics, his party won the elections, held a referendum on the new constitution, and he became its first president with full powers.

And first of all, de Gaulle ends the war in Algeria. This act of his earned him the gratitude of many French, but also the hatred of those who were forced to leave this colony, and after it many others. There were 15 assassination attempts on de Gaulle's life, but he happily escaped death. His indisputable merit was the technical breakthrough made by France in the post-war years. The French independently mastered nuclear technology and equipped their army with atomic weapons and their energy networks with nuclear power plants.

Charles's opinion on American monetary expansion surprised many at the time. Back in 1965, during an official visit to America, he brought Lyndon Johnson a whole ship loaded to the brim with dollars, and demanded their exchange at the official rate of 35 dollars per ounce of gold. Johnson tried to scare the old soldier into trouble, but he attacked the wrong one. De Gaulle threatened to leave the NATO bloc, which he soon did, despite the fact that the exchange was made. After this episode, America completely abandoned the gold standard, and we are all reaping the fruits of this today. The wise President of France saw this danger a long time ago.

In his name...

France appreciated its general soon after his death. Today, in the eyes of the French, de Gaulle is almost equal to Napoleon I. The flagship of the French navy, the first nuclear-powered aircraft carrier built outside the United States and without its help, the largest ship launched in France in 1994, is named after him. Today it is the most combat-ready ship in Europe.

Many thousands of visitors to France set foot on its soil at Roissy-Charles de Gaulle airport. Its ultra-modern design, which is combined with fantastic technical equipment, makes this airport a true masterpiece of architecture and technology.

One of the central squares of Paris - d'Etoile, Place des Stars, now bears the name of de Gaulle. Only knowing the desire of the French to preserve any details of history in every possible way, one can understand how much this means in their eyes. There is a monument to the general on the square (by the way, the French most often refer to him as “General de Gaulle”). Another square named after him is located in Moscow, in front of the Cosmos Hotel.

There is a lot more that can be said about this extraordinary man. But what is especially touching is the fact that he bequeathed to bury himself next to his daughter, who died early and was disabled from birth. It turns out that he was also capable of deep and tender love, this soldier and politician who was not afraid of anyone or anything...

Biography (en.wikipedia.org)

Childhood. Carier start

Charles de Gaulle was born on November 22, 1890 into a patriotic Catholic family. Although the de Gaulley family is noble, the de in the surname is not the traditional French “particle” of noble surnames, but the Flemish form of the article. Charles, like his three brothers and sister, was born in Lille in his grandmother's house, where his mother came every time before giving birth, although the family lived in Paris. His father Henri de Gaulle was a professor of philosophy and literature at a Jesuit school, which greatly influenced Charles. From early childhood he loved to read. History struck him so much that he developed an almost mystical concept of serving France.

In his War Memoirs, de Gaulle wrote: “My father, an educated and thoughtful man, brought up in certain traditions, was filled with faith in the high mission of France. He first introduced me to her story. My mother had a feeling of boundless love for her homeland, which can only be compared with her piety. My three brothers, my sister, myself - we were all proud of our homeland. This pride, mixed with a sense of anxiety for her fate, was second nature to us.” Jacques Chaban-Delmas, the hero of the Liberation, then the permanent chairman of the National Assembly during the years of the General's presidency, recalls that this “second nature” surprised not only people of the younger generation, to which Chaban-Delmas himself belonged, but also de Gaulle’s peers. Subsequently, de Gaulle recalled his youth: “I believed that the meaning of life was to accomplish an outstanding feat in the name of France, and that the day would come when I would have such an opportunity.”

Already as a boy he showed great interest in military affairs. After a year of preparatory exercises at the Stanislas College in Paris, he was accepted into the Special Military School in Saint-Cyr. He chooses the infantry as his branch of the army: it is more “military” because it is closest to combat operations. After graduating 13th from Saint-Cyr in 1912, de Gaulle served in the 33rd Infantry Regiment under the command of the then Colonel Pétain.

World War I

Since the beginning of the First World War on August 12, 1914, Lieutenant de Gaulle has taken part in military operations as part of the 5th Army of Charles Lanrezac, stationed in the northeast. Already on August 15 in Dinan he received his first wound; he returned to duty after treatment only in October. On March 10, 1915, at the Battle of Mesnil-le-Hurlu, he was wounded for the second time. He returns to the 33rd Regiment with the rank of captain and becomes company commander. In the Battle of Verdun near the village of Douaumont in 1916, he was wounded for the third time. Left on the battlefield, he - posthumously - receives honors from the army. However, Charles survives and is captured by the Germans; he is treated at the Mayenne hospital and held in various fortresses.

De Gaulle makes six attempts to escape. Mikhail Tukhachevsky, the future marshal of the Red Army, was also captured with him; Communication begins between them, including on military-theoretical topics. While in captivity, de Gaulle read German authors, learned more and more about Germany, this later greatly helped him in his military command. It was then that he wrote his first book, “Discord in the Enemy's Camp” (published in 1916).

Poland, military training, family

De Gaulle was released from captivity only after the armistice on November 11, 1918. From 1919 to 1921, de Gaulle was in Poland, where he taught the theory of tactics at the former imperial guard school in Rembertow near Warsaw, and in July - August 1920 he fought for a short time on the front of the Soviet-Polish war of 1919-1921 with the rank of major (in the troops of the RSFSR in this conflict, the commander, ironically, is Tukhachevsky). Having rejected the offer to take a permanent position in the Polish Army and returning to his homeland, on April 6, 1921 he married Yvonne Vandroux. On December 28, 1921, his son Philippe was born, named after his boss - later the notorious collaborator and antagonist of de Gaulle, Marshal Philippe Pétain. Captain de Gaulle taught at the Saint-Cyr school, then in 1922 he was admitted to the Higher Military School. On May 15, 1924, daughter Elizabeth is born. In 1928, the youngest daughter Anna was born, suffering from Down syndrome (Anna died in 1948; de Gaulle was subsequently a trustee of the Foundation for Children with Down Syndrome).

Military theorist

In the 1930s, Lieutenant Colonel and then Colonel de Gaulle became widely known as the author of military theoretical works such as “For a Professional Army”, “On the Edge of the Sword”, “France and Its Army”. In his books, de Gaulle, in particular, pointed out the need for the comprehensive development of tank forces as the main weapon of a future war. In this, his works come close to the works of Germany's leading military theorist, Heinz Guderian. However, de Gaulle's proposals did not evoke understanding among the French military command and in political circles. In 1935, the National Assembly rejected the army reform bill prepared by future Prime Minister Paul Reynaud according to de Gaulle's plans as "useless, undesirable and contrary to logic and history."

In 1932-1936, Secretary General of the Supreme Defense Council. In 1937-1939, commander of a tank regiment.

The Second World War. Leader of the Resistance

The beginning of the war. Before leaving for London

By the beginning of World War II, de Gaulle had the rank of colonel. The day before the start of the war (August 31, 1939), he was appointed commander of tank forces in the Saarland, and wrote on this occasion: “It fell to my lot to play a role in a terrible hoax... The several dozen light tanks that I command are just a speck of dust. We will lose the war in the most pathetic way if we don't act."

In January 1940, de Gaulle wrote an article “The Phenomenon of Mechanized Forces,” in which he emphasized the importance of interaction between heterogeneous ground forces, primarily tanks, and the Air Force.